Murrumbidgee: Hay - Boundary Bend: Day 7: Balranald 52 km towards the Murray River (93 km).

On this day I paddled from the Balranald Caravan Park to close to Canally Station. About 10km into the paddle I came across Yanga Station National Park and pulled out for a look around, before continuing onto the Balranald weir, where a portage was required.

After portaging, I continued on another 35 km, almost to Canally Station where I set up camp for the night - leaving just over 40 km for the last day.

After a windy afternoon and evening where the tent filled with dust, I got up at 5:30 begrudgingly into an unseasonably cold 3 degrees celsius. On these trips you develop routines so that you do not forget anything. Everything has its place and a time to be packed. Clothes are one of those things. I was quite happy that I had had a chance to wash my paddling clothes in the caravan park, but when it came to my shorts, they were missing. I thought about paddling without them, but considered what that might look like at the portage at Balranald Weir and decided to look near the washing lines again. In the strong winds all of my underpants were scattered and I think I would have looked like a kid at the annual Easter Egg Hunt, running round to pick them up - but i had missed my shorts. Putting on my wildlife hero cap, I looked in trees, gardens, around buildings and finally found them on the edge of a storm water drainage channel. I now had all my pants. A good omen for the day if ever there was one.

All packed, I said goodbye to one of the other campers who had gotten up for some early morning photography and set off at 7:15 drifting, just to get a feel for the boat. A group of ducklings entered the river from the caravan park and swam to the other side of the river. I watched them pass and then, gingerly took my first paddle strokes. Everything ached. My gortex jacket, though working fantastically with cut up stubby holders to stop water running down my sleeves at the top of the paddle stroke, restricted my movement. It took some time to get things right. The paddle to Balranald Weir was uneventful. I gradually warmed up, but felt the tiredness of the previous six days of 8 hours of paddling every day.

Ten kilometres downstream of Balranald is Yanga Station. http://www.nationalparks.nsw.gov.au/yanga-national-park/yanga-homestead/historic-site There is a good clay landing area just downstream of the station, which you can run up on (which I did), or just ease up to in a civilised manner. Tree roots make getting out and in easier. The station is well worth a visit. A working station until relatively recently, it is now part of the Yanga National Park as part of the cultural heritage of the area. All of the original buildings are there, most in original (now run down) condition. There are several houses, shearers quarters, washrooms (etc) and a very large shearing shed. The place is designed for self guided tours and walking around, it is impossible not to imagine what it would have been like back then. Camping sites with toilets are a few hundred metres away and there are many information boards around.

|

| Yanga Station: former working farm, now national park. |

|

| There is a huge woolshed... |

|

| ...with interactive displays, pens, presses and runs, worn by time... |

One story was of when the first bale of wool was taken from Poon Boon Station on the Wakool by the paddle steamer Lady Augusta and the barge Eureka. All in all they took 441 bales of wool in that first experimental voyage. The ladies of the station helped roll the first wool bale down the plank and onto the Lady Augusta. The bale was then hoisted up the masthead of the barge Eureka, a sailor sitting upon it, and on his giving the signal, a gun was fired, which was succeeded by "three cheers for the first shipment of wool on the Murray".

|

| Large information boards tell the history of settlement and the environment... |

|

| Reading through these, it becomes clear that the floodplains are unique... |

|

| ...they are the true Riverina, seasonal wetlands and rich pastures over summer... |

|

| ...able to sustain stock through the long hot summers because the spring floods soaked the soil... |

|

| "swarms with snakes"... many people still believe it does... with marshes and frogs in abundance, there is both habitat and food... |

|

| Early farmers showed remarkable foresight and understanding of the land they managed... |

|

| ...they recognised that rather than being a threat, flood were essential to the survival of their new way of life... |

|

| Flood runners angle down from the perched riverbanks into the forest, like short creeks that run from the river onto the plains... |

|

| The story of how the first bale of wool was collected by paddle steamers on the Murray darling Basin.. Boom times were to follow... |

There was also great information on the ecology of the floodplain and the history of water management schemes (and their planning) including what the first settlers thought, plans for eight locks and weirs to Hay and schemes to allow both irrigation and maintenance of the floodplains (by John Monash) as early as 1915 (before he was a general). Early pastoralists realised that plants can access water on land that has been flooded during drought. They argued that flooding was essential for their livelihood. They also maintained that forested areas should be kept, not just for red gum harvesting, bit as a refuge in drought, when all other feed was gone. Eventually, 4, not 8 weirs were built. Many areas now receive flooding, however some of the creeks which bring water into the forest where blocked in places like Narrandera. With not groundwater recharge possible in those areas, the forest systems that were there are dying. In the areas which do, the ecosystems are thriving, and towns like Balranald are poised to make the most of it.

|

| The Murrumbidgee floodplain between Hay, Balranald and oxley forms a mid system ecological storage that promotes biodiversity and has a history of complementary land use and environmental management. |

|

| Including agroforestry and protected land on farms... |

|

| The broad shelled turtle has a shell the size of a dinner plate... |

|

| ...whereas the short necked turtle is much smaller... both are threatened by foxes digging up their nests... |

|

| The Southern Bell Frog is the symbol of Balranald and has been adopted by the town, with frog sculptures throughout the town... |

|

| The soils in this environment have developed with regular flooding... |

|

| cracking deeply, filling with water and mulch during flooding, and then slowly releasing their stored water in drier times... |

|

| those areas which are not provided with environmental water for flooding are suffering, they are degraded landscapes... |

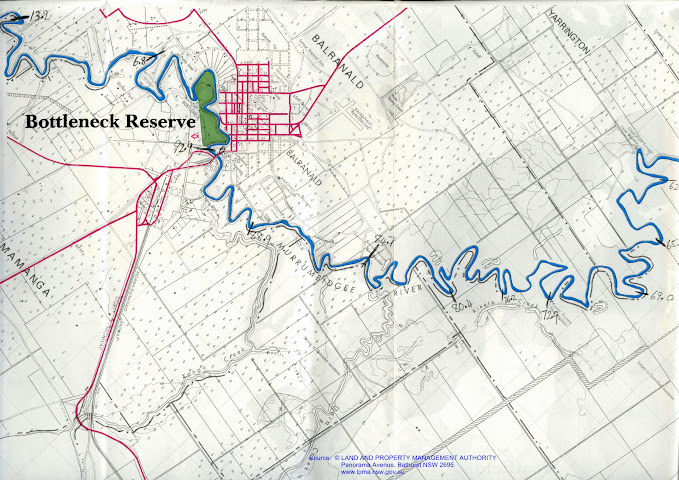

In the Millennium Paddle Blog they described the Balranald weir as a "P.O.P." Mike Bremers also found it the easiest of weirs out of the four below Hay, so I hoped to have a similar experience. I had looked up the weir on google maps and it looked as if there was an alternative to climbing the banks in front of the weir. The old river course was still there and had only been blocked in the middle (diverting the river through the weir). I paddled into this dead end and walked the route, but found it blocked by a dense copse of saplings (only visible as a green smudge on this iphone screen shot). I got back in my boat and paddled to the weir, getting out as close to the weir as possible and selecting the least steep bank. There was no landing, or flat area so there was a real danger of losing gear whilst unpacking the boat. Dragging a fully loaded boat up a bank is not fun. In these situations, paddling as a group would make such takes much easier, however I do think that for a river that is being promoted as a canoeist's river, they could modify the bank a little. A 300 metre 'walk' later there is a steep bank to slide the boat down to get to the river. I don't know if I recommend holding onto the boat and risk being pulled into the drink, or letting it go and possibly having to swim after it. The whole portage took me about an hour. I was glad it was my last one.

|

| An aerial shot of Balranald weir. You can see the now blocked, original channel of the river. There is no easy option at his weir if you are alone. A large new cyclone fence mean a long walk around the weir infrastructure is necessary before relaunching. A potential short cut on the southern bank just before the weir is not an option as the whole bank downstream has been layered with sharp bluestone which would damage the boat. The long walk is unavoidable. |

|

| Block and tackles were traditionally used to lift heavy weights and are still in use on yachts and sailing boats. The more times the rope passes through the 'block' of pulleys, the greater the mechanical advantage (though some of the advantage is offset by friction). A lightweight block and tackle might be useful thing to help get up steep banks, or over snags on the Murrumbidgee. Strong light-weight gear is available in sailing shops. Graphic: Wikipedia. More information on how pulleys work. |

After the weir the river became more snaggy again, but it was to get worse. About twenty kilometres downstream of the Balranald Weir, snags stretching all the way across the river are the norm. I rode over many logs, ducked under others and pushed through the small branches of some. If you don't have to worry about your boat getting scratched, its a lot of fun, but it will keep you on you toes. That 'bad' section is narrower than the rest of the river. I suspect that it is younger, that the river has moved its path there only in the lat few hundred years: it is yet to develop the wide high banks so typical of the rest of the river. For a canoeist, it is a bit like paddling down the narrows, but in a river that is half the width and with ten times as many snags.

Again, sea, wedge tailed and little eagles were frequent, however corellas and cockatoos have appeared as well. The environment becomes more Murray river like, the closer you get to it, it seems. What did surpass me was seeing a red kangaroo. i did not know that their range extended this far South. It was a small one, as they often are on the limits of their range.

I found camp after having paddled about 52 km, which I was extremely happy with, given the hassle I had with the portage and the time I spent at Yanga Homestead. It has a small beach to land on and an area safe from trees. Behind it are piles of timber, up to two metres high, washed through in high river (not the place to be then). There are sawn tree stumps, and on these I made by evening meal. From camp I can see the sunset over the plains. I am not far from Canally Station and although I cannot see it, I can hear some children's' voices in the distance. Around my camp are screeching cockatoos and once darkness falls, the sounds of kangaroos moving through the woody understory.

|

| My camp for the night was a comfortable one. I even found a natural jetty to climb out on... |

|

| At the top of the bank were several large stumps, which served as tables... |

|

| View from camp was to the West, making use of the evening light... |

|

| ...as the sun descends, quiet settles upon the Murrumbidgee River. |

|

| With clear skies, sunset was golden, the slight movement of the river appears mystic... |

|

| My bush kitchen... |

There are not many photos today, as my micro SD card fell into a deep crack in one of those stumps. Try as I may, I could not retrieve it. I have decided that it can become a fossil and amuse some future generation… or not. At least i am saved the hassle of uploading. Mind you I thought that there were some pretty good pictures on that card from today. "Them's the breaks" as my old mate Sharky would say.

Tomorrow is the last day (43 km approximately). I hope to break out into the Murray in the early afternoon. Its been a great trip, well worth doing, just pack lightly, plan generously and come well prepared for weirs.