Murrumbidgee: Hay - Murray River (near Boundary Bend) Day 8: arriving at the Murray River. 44km.

|

Mike Bremers: Murrumbidgee Canoe Trip 1995-2008

My camp was at the 48.7km mark (52km by GPS) on this map. I got away early and soon passed Canally Station (which, like Pevensey Station, has a paddle steamer named after it).

|

|

Mike Bremers: Murrumbidgee Canoe Trip 1995-2008

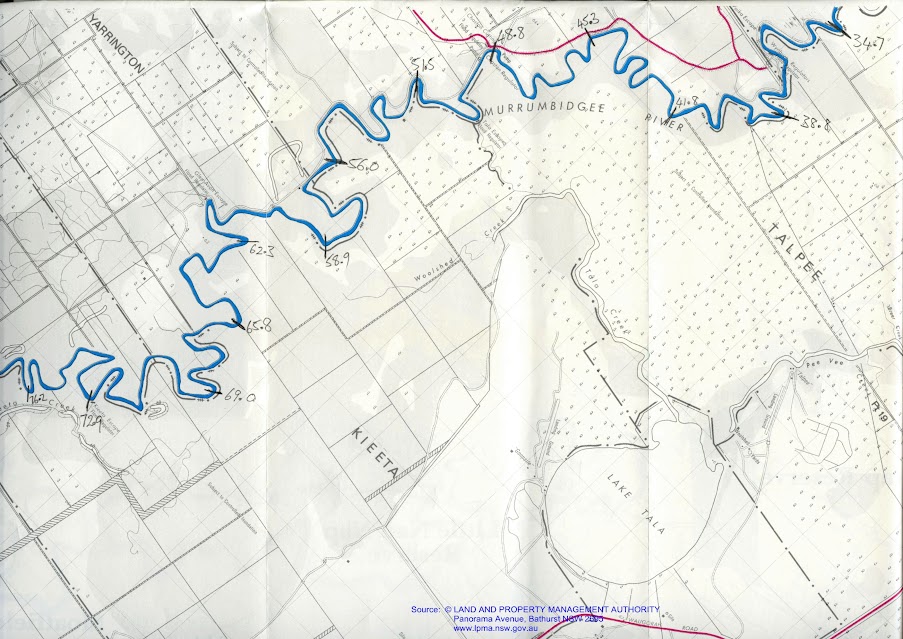

The river twists and turns in this lower section. Sturt, exasperated, complained that the river followed every point of the compass at some stages (around the 50 and 80 km mark on these maps).

|

It had been a cold night, but I kept warm in my sleeping bag by pulling the hood down over my head until it resembled a frog. Out of the slit between the hood and the body of the sleeping bag I could breath and catch a glimpse of light. I feel claustrophobic when all the drawstrings are pulled tight, fearing that I could not get out in a hurry, or that the strings will get wrapped around my neck and strangle me, but with this arrangement the hood kept me warm without the feeling of being trapped. Other than the normal twists and turns associated with sleeping on the ground, I slept well. So well, that I slept through the first alarm that went off in the morning and it was only by chance that I awoke 20 minutes later at 5:50am to find the birds in full chorus and the light strong enough to make out everything without a torch. I packed methodically and efficiently, so that in 20 minutes, all of my gear was beside the boat, ready for stowing away.

|

| Morning light on my camp near Canally station. |

I made breakfast, dressed in my paddling gear (which had dried overnight), secured the solar panel and the clips to my battery behind my seat in the cockpit. The log beside my boat meant that I could get in without muddy feet, which was nice. I pushed off and than poked around till I found a way out between the saplings, eating breakfast gradually as I eased into padding. The morning was the coldest yet, only 3 degrees, so I was well rugged up, with a heavy neoprene spray deck, gortex jacket and beanie. I used a cut up stubby holder to stop water running down my sleeves and into my top. They worked surprisingly well.

|

The PS Canally: named after Canally Station and now under restoration in Morgan S.A. was known as the 'greyhound of the river' ,however not without controversy, as this report on a race between it and the PS Alexander Arbuthnot in 1913 shows.

3/9/1913 - Riverina Recorder Steamer Rivalry - The Barham 'Bridge' says that much rivalry exists between the connections of the Arbuthnot and the Canally as to which is the fastest boat and in a speed trial recently the owners of the latter claimed that their vessel was superior in this direction. The engineer of the Arbuthnot could not develop the speed which he knew his boat to be possessed of, and on examination of the smoke box it was discovered that some individual (presumably a rival) had dropped a brick down the funnel. The draught from the furnaces being considerably interfered with in consequence. Given a fair trial the crew of the Arbuthnot reckon they can beat anything on the river. (Source: Friends of the Canally).

|

|

| The river is always changing... |

|

| in the morning, the sunlight almost invites you to discover each bend... |

On the water there was a steady current of between one and one and a half kilometres an hour, seemingly faster in some places and slower in others. Reception was good throughout the day, as I moved out from the Murrumbidgee floodplain and into the Murray Darling Basin depression. The difference between paddling down the Murray and the Lower Murrumbidgee is that in the later you are paddling through an established ephemeral wetland. When the ‘bidgee floods (which naturally happens with the snow melt in September and October) it runs into parallel overflow channels which run for hundreds of kilometres – some for as far upstream as Narrandera. These then feed into smaller channels and lake systems. Some of these are used again today to maintain the natural landscape and environment in a healthy condition, which is why there are so many sea eagles here: their hunting is not confined to the river channel, but includes the lakes and wetlands around it. As I neared the Murray the last of these re-entered the river and the landscape became drier. The air smelt different, drier and the species of birds changed, there were more cockatoos, corellas and galahs and there were less eagles, kangaroos and emus. With every paddle stroke I was nearing the Murray – all my senses told me so.

|

| which may open up into great straights... |

|

| or a tangle of snags... |

The map was less convincing. The river twists and turns the whole way from Hay to the Murray River, but in the last section of the Lower ‘bidgee it seems to put in a special effort, as if it was saying ‘please let me do my own thing a little longer’. There are two points a little before and after Marnie Station, where the ‘bidgee has straights of a kilometre at every point of the compass, first East, then North, then West, then South. It left Sturt exasperated during his exploration of the river, “…(the river) in its tortuous course, swept round to every point of the compass with the greatest irregularity.”

|

Mike Bremers: Murrumbidgee Canoe Trip 1995-2008

Detail showing how the river seems not to be able to make up its mind which direction it wants to flow in...

|

|

A plan by Sir John Monash proposing the possibility of irrigation and wetland coexistence.(Yanga Station Display).

|

|

| Fisherman's shack. |

Around Manie Station the snags were particularly bad. About 75 km downstream from Balranald a tree trunk with a diameter of almost a meter, completely blocks the river. I found a gap big enough to let my sea kayak through at the top end of the snag, however at lower water levels this would not have been an option and a portage would have been unavoidable. I avoided portages, because they meant unloading and reloading the boat (probably in the mud). In the next ten kilometers so may tree blocked the river, that I lost count. Most were small enough that I could push through the smaller twiggy branches, duck underneath, or slide over with a run up. On one, however, my run up was not fast enough and I spent some moments with both ends of the boat in the air, like a balance scale. I managed to continue by pushing down onto the snag, lifting my boat in the process. It was impossible to paddle off, or to pull my self over. Those few moments where I was stuck, with my tail rudder slowly catching the current and threatening to turn my boat sideways, seemed much longer than they actually were. My heart beat loudly, adrenalin pushed already tired arms and an exhausted body to go harder than ever seeking a release, which eventually came. The escape feeling must be similar to that in a hunted animal. It takes some minutes to calm down again and labored breathing to blow off all the accumulated carbon dioxide. I wondered how Sturt managed such problems in his whale-boat. Indeed, even in the higher river that he had (“We were carried at a fearful rate down its gloomy and contracted banks.”) he will have had issues with large snags and blockages of debris.

|

A large tree completely blocking the Murrumbidgee. I was able to slip around in a metre sized gap on te left hand side.

|

|

| Here, an impressive clay reef stubbornly refuses to be eroded on the outside of a bend in the Murrumbidgee. |

I passed five stations today, of which Canally was the first and the prettiest. It was a well maintained, white painted wooden weatherboard building with verandahs on all sides. In front of the house and to one side stood a windmill and a water tank on a tower, providing water pressure for the house. The tower was overgrown with a flowering vine, which gave a sweet scent to the air and would have provided a home to small birds, as well as keeping the tank water cooler in summer. It was from this homestead that I could hear the children’s voices last night. It struck me that those kids would have a good childhood; the place looked cared for and they were surrounded not only by fertile land, but the most beautiful natural environment. Waldara could not be seen easily from the water, only water tanks and farm machinery gave way its presence. Tarana was a well kept large traditional looking station, with large sheds, at least the equal of Yanga Station (now preserved in as part of a National Park further upstream); the only difference was that this one was cared for and still in use.

Succession is a problem on farms (ABC report), many things have to be right for the younger generations to be able to take over from the older. Some manage it: in Yanga Station, one of the signs spoke of a station that had been in the one family for well over a hundred years. In these days of increasing foreign and corporate ownership, it must be a worry of many land-owners that the past and the environment they have cared for will be looked after just as well by the people who follow in their footsteps.

|

| Nearing the junction. |

Just before Manie Station, there was a new and narrow cutting, but the water was so shallow here and the possibility of being wedged against the snags at its outlet into the main stream made me decide to be cautious and not take that short cut. There was a fair drop in the river here, I could tell from the difference in water level between the top of the cutting and the bottom. I calculated that in the 400 km I had paddled that the river had dropped around 20m, that is 5cm a kilometer. In the kilometer that this cutting would have saved I noticed about a 20 to 30 cm drop, which means that the river must be pooling behind clay reefs in many other places. The kilometer past Manie station was full of snags and the fast current through here made paddling it like doing a slalom course. It could not be taken slowly. It had to be done at full power to have maximum steerage and the speed to go over small horizontal branches. I did get through. Manie station is set well back from the river. I was able to see tanks, but little else. A later look at Google Earth, confirmed its location, well back from the bank.

In this area, stations tend to be built on areas of red soil, as the pioneers learnt that these areas tend not to be flooded. Weimby, the last station before the Murray was no exception, again, the house cannot be clearly seen, but you will know that you are there when you see the rusty old remains of an old corrugated iron water tank which has been rolled to the river’s edge, along with a collection of other rubbish. It used to be common practice for farmers to dump their old vehicles off the river bank and watch them rust away. It must have been a period of detachment form the environment, when motorization, the lure and power of the combustion engine, made people feel that they did not need the environment, only enough machinery to bend it to their will. Thank God, those days have passed and rubbish dumping on this kind of scale is a rarity now.

|

Just before the junction I came across three old wooden boats with single cylinder engines. The three gentlemen owner-builders had come together from different corners of Victoria for an outing from Boundary bend and had pulled up for lunch a kilometre up the Murrumbidgee. As I passed them they had just lit a fire for lunch and invited me to join them, however with only a kilometre to go and the knowledge that Ruth was waiting for me, I was in no mood for a long break. It is only possible to travel about 4 to 5 kilometres up the Murrumbidgee in a boat like these before the passage is completely blocked by snags, however even this short foray awakes nostalgia. Enter into the Murrumbidgee and you step into the past, a time when white Australia was young, naive and hopeful, when the whistle of a paddlesteamer meant civilisation and the chance of prosperity, success depended on ingenuity, luck, and the whims of a river fed by storms and snow 1000 km away.

|

My camp by Canally Station was the end of the pure Lower Murrumbidgee Seasonal Wetland; bits of it reappear now and again, but farmland, with its sheep, goats and cattle are much more prominent. There is a change in the birdlife too. I saw no more of the sea eagles that have been so much a feature of this trip on this day and fewer pelicans. Corellas, cockatoos and galahs became more common, the crowns of the trees bright with their audacious character. The air smelt different too, it was a dry air, that told of drying soil and warned of the approaching summer. It was as though the river had been a playground and here were the realities of life. The ‘bidgee, with all its cheeky character and life was about to enter a river of a whole other scale. The teen was about to meet its parent. The junction was near.

Not that I was keen to end the paddle, but after 8 days and 400km it was great to reach the Murray.

|

The confluence of the Murrumbidgee and the Murray Rivers. Fishermen seemed to be having quite a bit of luck where the current swirls as the two rivers meet.

|

It happens suddenly. One last bend to the right, shorter than expected and the grey waters of the ‘bidgee join the green waters of the Murray. Swirls show where their currents meet in an unavoidable embrace. On the opposite bank I see my girl. Ruth has driven, as she always does, hours to meet me. I break into a sprint. A feeling a happiness, relief, satisfaction and privilege run through me. I feel privileged to have paddled the lower ‘bidgee. Not many people seem to have done it in the last few decades. It is the forgotten river, and all the more special for being so. The snags that make it so difficult, also protect it and provide home to so many animals above and below the water. Increasing my pace till my arms ache, I build my speed both as expression of my feelings, to show that I am well and to launch up on the bank on the Victorian side of the Murray. My boat makes a crunching sound as it slides up, over the sand. I release the spray deck and stagger to an upright position, walk to my girl and we hug. The lower ‘bidgee has been a challenge, but worth every kilometer.

|

| Hanging up gear to dry before loading my boat for the trip home to Echuca. |