|

| Mike Bremers: Murrumbidgee Canoe Trip 1995-2008 |

|

| Mike Bremers: Murrumbidgee Canoe Trip 1995-2008 |

|

| Mike Bremers: Murrumbidgee Canoe Trip 1995-2008 |

Bush camp

Tree roots exposed by the river

|

| Great Cormorant: www.flickr.com |

|

| Museum of Victoria's Field Guide App for NSW help identify animals. It even has the calls of birds and frogs. Field Guide to NSW Fauna is a valuable tool for anyone with an interest in wildlife. Use it in urban, bush and coastal environments to learn more about the animals around you. |

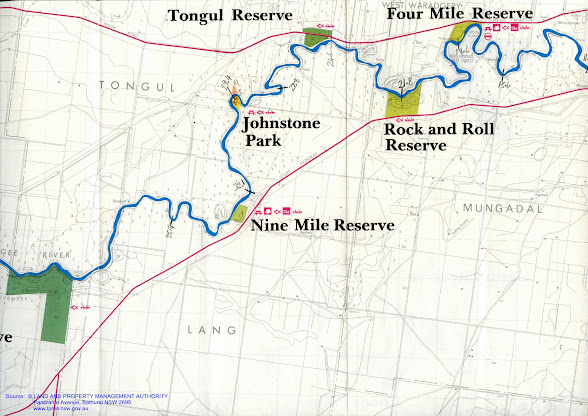

Now about 12 km into the paddle. The GPS is refusing to do anything but show it's start screen. Seems to have been an expensive mistake. Just have to wait a lunch break and try and see what I can do. I remember reading something about taking the batteries out and holding the on off button and then re-inserting the batteries and it should be right again. But I'd better wait until lunch when I have dry hands on moisture could get into the device. There is a fresh wind coming from the south-east so most of the time I'm heading into it. Following the map and the kilometres written into it, I am at about the 16 to 17km point - almost at Gordon Point at the 4 mile reserve.

Near Four Mile Reserve I come across an old shearing shed in the Wooloondool State Forest. It seems to be in the process of progressively being swallowed up by the bush surrounded it. The shearing shed is located in a convoluted peninsula with the river forming a natural boundary for stock on all sides except for a narrow 'bridge'. Early settlers often used the land to their advantage like this. In Echuca, what is now the Scenic Drive, used to be a holding paddock for police horses and near Kulcurna Station on the lower Murray, a similar landform was used to trap wild horses.

“It’s like the old days of camping when you and the family take the dog, park the trailer, set up for a week, live on fish, and it costs you next to nothing.”Wooloondool, part of Murrumbidgee Valley National Park, is within easy reach of the town of Hay, and it’s an ideal place to camp. Many set up camp at Wooloondool as it’s a great place for fishing - yellowbelly, redfin, brim, catfish, and carp, as well as crayfish during the season, can all be caught here." Wooloondool Reserve

I have heard the beautiful calls of the Pied Butcher Bird through the forest. This bird is a bit of a conundrum. It looks like a stunted magpie, but instead of warbling and 'carolling', it whistles. Its song reflects off the gum leaves in the canopy and carries well over long distances. Despite its song and good looks, it did not get the name 'butcher bird' by chance, it has a habit of spearing its prey on thorns until it is ready to eat them. It hangs its meat to keep it fresh. The river this morning has also been home to pelicans wheeling into the sky on my approach, great cormorants, pied cormorants usually high in the dead trees that line each bank, australasian darters struggling to fly with crops full from the last dive, tree martins, brown treecreepers and pacific black ducks in their hundreds.

|

Android App: The Lower Murrumbidgee floodplain is a unique area. Use this app to learn about the Lower Murrumbidgee Floodplain and explore both natural and cultural wonders of the area. Investigate the diverse plants and animals of the Lowbidgee with over 100 species profiles presented and the ability to report a species you have seen. The app also includes information on things to do, places to visit, towns, national park information and a map. Visit the app's gallery to take the opportunity to share your Lowbidgee photos. |

Approaching the weir the river nears the top of its banks.

Magnificent hollow in an old river red gum.

Trees flooded by Hay Weir provide habitat for water birds.

|

| White breasted sea eagle: Wikipedia |

Watermarks showing normal water level

Spoonbill

White breasted sea eagle

Hay Weir appears like a gateway in the distance.

On the other side ther are no more dead trees

And the banks are natural once again.

|

| Black Winged Stilt: Wikipedia |

There was a lot of water coming out of the weir. The flow at least in the first section is as good as the Murray. The wildlife seems less disturbed, though remains timid.

As the afternoon rolls on the sun comes out more, creating sparkles on the water's surface. It is a pleasure to paddle this section of the 'bidgee.

My first beach since leaving Hay.

The Lowbidgee winds through farm...

And forest...

|

| PS Pevensey... named after a wool station on the Murrumbidgee River. |

Steamers were a connection with the outside world. Not only were they good for business, but they also brought visitors. Some were churches, like the PS Etona, and performed weddings and baptisms along the rivers. Others were shops, selling pots and pans and flour. Still others were fishing boats, like the PS Canberra and kept their fish fresh is netted half sunken barges towed next to the steamers. The PS Pevensey was one of the grandest of the wool boats. Wool bales were stacked until the captain could only just see the river and even higher in the huge barges behind them. They allowed this area and the people who lived in them to prosper and establish the great properties that still exist today. Rail brought the end of the river trade, just as road transport led to the closing of most branch lines almost a century later. Now the Murrumbidgee is full of snags and the weirs placed on this river do not allow the passage of boats as they do in the Murray. More is the pity.

Not far after Pevensey, I found a large beach with enough room to pitch my tent out of reach of dangerous branches. I turned around, took aim and paddled hard so the the first half of the kayak would launch onto dry land. I then pulled up my boat, out of reach of a possibly rising river (following yesterday's rain and the amount of water that was being allowed through the weir.

After setting up the tent, I settled into cooking, determined to eat my way through my boats food stores. I am sure I have brought too much. I usually do. Sitting watching the sun go down, whilst dinner cooked was very peaceful. It is the time of day when birds seem to wake up again,with either the urge to be social, or to eat - it is difficult to tell which is the case, they seem to be doing both.

Spotted doves were feeding on the grass seeds on the beach, yellow plumed honey-eaters squabbled, Murray Rosellas found young buds on the red gums, biting them off to get to the sweet sap that feeds them. There must be a grey shrike thrush. These are a beautiful to listen to. Their song is almost as varied and inventive as a lyre birds'. Two strong looking young bulls came down too. Luckily they were not too curious. Better pack up well tonight though. Tomorrow I hope to reach Maude.

| Boats loaded with wool bales at the Echuca Wharf. |

On this section...

There is..

A sense of isolation...

Ther is just you and the river...

Pevensey Station: fuel drums.

Pevensey Station

|

| My campsite near Eulalie Station, just downstream from Pevensey Station. |

|

| Wahlenbergia stricta: native bluebell. A plant which has survived from Gondwana times, it exists in South America, Australia, South Africa and New Zealand. |

|

| Murray Rosella: the yellow form of the crimson rosella. |

|

The spotted dove is native to India. It was introduced to Melbourne in the 1860's and quickly spread, sometimes replacing native doves (wikipedia) .Spotted Doves feed on grains, seeds and scraps. The birds are seen alone or in small flocks, feeding mostly on the ground (birds in backyards). |