Day 6: Maneroo Rd. to Emily Rd.

298 - 387 (89 km)

After a good nights sleep, I woke with the morning light, the soft gentle light before the sun rays actually reach you. The birds were in full song. I enjoyed listening to them. Their chorus was similar to some tropical rainforest CDs that we have, the kind that is meant to be calming and fill you with awe at the beauty in the world. There were birds calls amongst the chorus that I did not know, which made it feel exotic and even more enjoyable. As I packed, I listened to the morning news on my portable radio (more reliable than mobile internet in the bush). I learnt more about the latest violence in the world and people's efforts to contain it, but really, I was after the weather report. If there was to be more rain than sunshine, I would have to put on all my layers again and if it wasn't and I did, then I would cook. It turned out that I needed to guard against the sun, rather than hypothermia, as I had had to yesterday. It had not rained during the night, which provided me with an opportunity to hang up my sodden clothes on the rescue rope I had brought with me for the upper Goulburn. That seemed a world away now. I had not needed it, but it made an excellent clothes line. With a shudder I pulled on my still damp gear, knowing that once I was on the water they would get wet anyway and packed away my things.

|

| I awoke to the sound of bird song so rich and varied that it was if I was in a tropical rainforest. Witnessing such diversity is pure joy. Despite knowing my birds pretty well, I couldn't name them all: suffice to say that there was big and small and everything in between. I felt that this was what Noah's Ark must have sounded like and became aware of a common bond (greater than race, politics, or country) with anyone else who has ever camped in the bush and loved it. |

Packed and ready to go on what was to be my second last day. Two little white dogs came down from a nearby farm to make sure I was leaving.

Breakfast was boat-side. The bow is the strongest part of the boat and made a useful seat as I dipped into my food hold. Keen to get into my tent and out of the rain as fast as possible, I had only had a soup last night and now had a healthy appetite. Muesli, then tomatoes, salami, a piece of cheese, some diced peaches and a muesli bar. Eating big turned out to be a good idea, the energy keep me going for 30 km, when I had my next snack. As I was pushing off from shore two little Scottish terriers came down to make sure I would go. The growl the older one gave could have come from a much bigger dog: respect. I looked for the owner, but with no-one in sight I pushed off, noting the time. It was 7:30 am: pretty good. The current caught the bow swinging the boat downstream and I was off.

Mornings are lovely times to paddle. The light was soft, the day still cool and the birds calling. Reason enough not to rush. Another reason though, was that my hands were still tender from the day before. This takes a little while to go away, but go away it did. Just as I was settling into my paddle, I came across my first cutting for the day. Cuttings are where the river has found a new course. They are shallow and usually full of snags, but they can also save kilometres. This section of the lower Goulburn has many hairpin bends, some right next to each other, like folded cloth. In some cases the river cuts right through these layers and in others, you have a to go all the way around. I took many cuttings today. Each of them gives you an adrenaline burst. You can only see how clear they are when it is almost too late to turn back. Goulburn Murray Water have put large bluestone rocks in the cuttings. I think the idea is to keep water flowing through the main channel, except at high river and to stop the river eroding more when it does.

Cuttings are young river beds. They are places where the river has found and established a short cut. They are rarely as straight as this one, but can save kilometres from the days' paddle. They are also interesting to follow. You never know quite what you will find. Occasionally, they are narrow and fast flowing, which makes a nice change from the broad, slow main channel. However they can also be shallow, snaggy, or blocked by tree trunks that stretch from side to side. Together with old river beds, they help drain flood waters resulting from summer and winter storms. And deliver fresh water to isolated billabongs and wetlands, maintaining a healthy diversity throughout the flood plain.

In this section of the river the Goulburn often doubles back on itself. During big floods, when the river breaks its banks and flows straight over the land, it creates shortcuts called cuttings. With a slightly higher river than normal water was flowing down these again. It was an opportunity to explore which I could not resist.

The Lower Goulburn National Park Notes provide insight into life in this section of the river and a quite good map.

The Lower Goulburn River corridor has strong ecological integrity and is a recognised biolink through the landscape. In recognition of its unique natural, recreational, scenic and cultural values, the Goulburn Heritage River was declared in 1992. Kanyapella Basin and the Lower Goulburn River Floodplain are both listed under the Directory of Important Wetlands in Australia. The Lower Goulburn River National Park makes significant contributions to improving the representation of a number of Ecological Vegetation Classes (EVCs) in the Murray Fans bioregion, including Riverine Grassy Woodland, Sedgy Riverine Forest and Floodplain Riparian Woodland, as well as protecting areas of endangered Plains Woodland and Riverine Chenopod Woodland along the River Murray.

The Lower Goulburn forests are particularly important habitat for a number of significant fauna species, including the Squirrel Glider, Brush-tailed Phascogale and Barking Owl. Kanyapella Basin provides habitat for a number of threatened bird species, including the critically endangered Australian Painted Snipe, the endangered Bush Stone-curlew and the vulnerable Royal Spoonbill, Diamond Firetail and Musk Duck. Flora species of note include the endangered Grey Billy-buttons, Small Scurf-pea and Jericho Wiregrass.

The Lower Goulburn River National Park contains a number of known sites of Aboriginal cultural heritage including scarred trees and artefacts along the riverine forests, and cooking mounds at Loch Garry and Kanyapella Basin. The national park should be managed to protect these values.

|

Following the rain, the rubbish that had been washed down the storm water drains and into the rivers was a real issue. The drains had also washed organic pollutants into the river. You can tell when this happens, because foam builds up on the snags. I was keen to paddle ahead of this, estimating that with a 2 km/hr current and the beginning of rain being 24 hours ago, that I would have to paddle 48 km to do so. This turned out to be about right. It did not bring me past the last of Shepparton's floating televisions though. Why would people throw their TV's into the river and why was this habit peculiar to Shepparton? For a visual presentation of environmental issues facing the Goulburn River near Shepparton, see this presentation by riverconnect.

Most of the mature redgums had at least 10 hollows and some had over 30. These old trees are the elders of the forest, its sentinel guardians, trees of life.

In an interview by Ecos Magazine, Matthew Colloff, a principle research scientist at CSIRO Ecosystem Sciences said...

Do you feel hopeful about the future of river red gum forests?

I know that I would have felt very differently about the future of river red gum forests if I hadn’t gone to visit central Australia. What I see there is that the trees have contracted their range from millions of years of a drying climate and are now confined to a narrow strip along the rivers. They don’t form extensive forests like they do along the Murray, so people don’t have a timber commodity association with them that they did in south-eastern Australia. People view them differently. They are sacred. They provide a refuge for animals within an otherwise harsh and arid landscape.

That tough enduring relationship provides a model for how we can learn to view them under climate change. Our landscapes will alter.

|

On one stretch I startled and set off the biggest ruckus from a mixed flock of 100's of corellas and cockatoos. The trees in the area were tall and healthy, mature redgums. It seemed like the stretch of river was their nesting area. I once saw a poster which shows a river redgum as habitat for the animals in the forest. 'Tree of life', they called it. Frogs, geckos and spiders lived under the thick bark, where it loosens from the trunk. Insects and koalas fed on the leaves. Possums, cockatoos, galahs and corellas fed on the flowers, buds and gum nuts. Goannas and snakes hid in hollows to sleep. Wombats dug their nests beneath the roots... And so on. I counted around 10 hollows on most mature trees, with some having easily more than 30. Young trees don't have the hollows, showing why it important to have some older trees in order to maintain a healthy forest ecosystem. Using Swedish technology foresters can selectively harvest only the trees they are interested in and create strong forests which support wildlife and in contrast to clear felling of areas, trees are available every year, not just every 50. It is catching on in Australia, a redgum logging company in Barham works this way.

Today I saw my first carp. Carp are a huge problem in Australia's inland rivers. Introduced as game fish unsuccessfully for the first five attempts, till a super carp variety was bred near Swan Hill. In the floods of 1974, these escaped into the Murray and spread rapidly. As a child I can still remember the smell of rotting fish and the size of their bodies that covered the banks after the floods receded. You couldn't go near the river for a month. Since then they changed the Murray, they ate the water plants and made the water more turbid by working their way into the river banks looking for food. Attempts to restock Murray Cod and to re-snag the river to improve conditions in favour of native fish seem to be paying of in the Murray, however I had no idea how successful they had been in the Goulburn. In contrast to the Upper Murray, water plants are plentiful in the Upper Goulburn. Fishermen tell me that now the most common fish they catch is Murray Cod (but they have to give back everything under 60 cm and there are strict bag limits). They still catch carp and big ones too. The Chinese community seem to value these. Talking to one fishermen from that community, he said that the little ones have too many bones, but the big ones are good eating.

|

| Source: Talking Fish: Making connections with the rivers of the Murray Darling Basin. |

|

|

Will Trueman on what fish used to live in the Goulburn and in particular, trout cod.

|

| Massive pile ups of snags are reminders of how high the river can rise when in flood. |

The only people I have come across on the river have been fishermen, but even so, I would probably only have come across 30 or so in the 387 km I have paddled on the Goulburn so far. It is quiet river, a beautiful river and always ready with a surprise. I hit snags whilst photographing a couple of times today. As you can imagine, this is destabilising. They are difficult to see in the slow moving water and in the quiet and lonely atmosphere, quite a shock. It is the equivalent of someone scaring you when you are just about to fall asleep.

|

| McCoy Bridge, where the Murray Valley Highway crosses the Goulburn River just south of Nathalia. |

Map showing river access point 1 km downstream from McCoy Bridge, where the Murray Valley Highway crosses the Goulburn River. |

Not far downstream from McCoy Bridge the bank is littered with saw logs. How long have they been there? The last logging steamer operated out of Echuca up until 1957 (P.S. Adelaide) of Murray River Saw Mills. For an insight into life in saw mills in the Murray Darling Basin see Arbuthnot Sawmills Pty Ltd and the PS Adelaide's story visit Port of Echuca. In their heyday, over 1000 people were employed by the saw mills in Echuca (Echuca Historical Society).

|

|

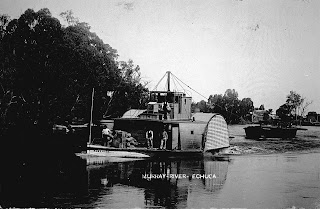

| PS Adelaide unloading logs at Murray River Sawmills in Echuca just upstream from the bridge. Source: Museum Victoria. |

|

| PS Alexander with a full head of steam, passes PS Hero which has an outrigger log barge in tow. Frank Tucker |

| Murray River Sawmills Echuca. PS Adelaide. Australian War Memorial. Bean Collection. |

The outriggers were only ever towed upstream empty. For the downstream forest they used an insider barge. The boats belong to the Murray River Sawmill. The outrigger barges in the foreground were used to bring logs from Barmah forest. Two paddle steamers can be seen on the far river bank and a barge for carrying logs is visible near the bank in the foreground. The closest steamer is the Adelaide, she worked for the mill from 1872 until retirement in 1958.

"Growing up in Echuca, a trip to the Barmah Forest"

A personal story of logging on the Murray River in the days of the paddle steamers: by Terry Kennedy 2010.

There were two sawmills, ‘Evans Brothers’ and the ‘Murray River Sawmill’; they exploited the red gum forest resources along the river. Many of the roads and bridges in those times were six ton limit and did not allow road transport to the same extent as today; the logs were often transported to the mills by river from landings along the river adjacent to the forest leases the mills were working. Before each season when the river levels were low, the paddle steamers cruised the river routes, they used their steam winches to removed snags, other obstructions and navigation hazards from the river, at various points along the river woodcutters set up stockpiles of wood to refuel the boats. When spring came and the river levels rose the logging season got underway.

On Sunday nights the paddle steamer Adelaide under the command of Captain Freeman set off up the river with the barges in tow, making her way to the loading sites. Because the steamers were voracious wood burners they needed to stop to take on fuel at depots on the way...

I went to work with Bill many times before I started school, I loved the various adventures, such as helping with the ice deliveries before people had refrigerators, grooming the draught horses and driving the road grader, but this story is about the best adventure I ever had with Bill. On Sunday afternoon after our family Sunday roast lunch. Bill and I made our way down to the barge; the barges were moored to trees on the riverbank near the bridge that connected Echuca on the Victorian side with Moama on the NSW side of the river ‘The Iron Bridge’. The crew of each barge consisted of two members; on our barge the other crew member was Jacky Boyd. Jacky and Bill loaded the supplies onto the barge and checked the chains and other gear needed to secure the logs for the trip back to Echuca. The crew accommodation on these barges was very primitive, at the stern of the barge below deck a part of the hold was partitioned off, it contained two beds, cooking was done in the open hold on a brazier made from an old oil drum that was on a base of bricks to prevent fire damaging the bottom of the barge. Each barge had a dinghy that was used to row ashore or to row ahead to warn punt-men or bridge operators that the barge was coming through; it required a lot of skill to row the dinghy. Bill was a very skilful river man, and an excellent oarsman; he could make the little dinghy glide over the water at a great rate.

After the preparations were complete the steamer took up the towline and barges were allowed to drift into mid-stream, we were on our way. Darkness was falling the brazier was burning Uncle Bill was preparing our evening meal of barbecued chops and sausages, the crews of the other barges had joined us and we sat down to a great feast.

The paddle steamer thumped her way upstream the river darkness penetrated by a large light on top of the wheelhouse, the relentless beat of the paddles soon lulled me off to sleep, snug in my camp bed in the barge cabin I saw no more of our trip up stream. By dawn we had arrived at the loading site; the barges were positioned to receive their cargo of logs, soon the loading began.

Red gum logs do not float; they need to be supported before they can be loaded onto the barges. Because the return journey to Echuca was downstream the logs were not loaded into the holds of the barges but were attached by chains to great outriggers consisting of large logs lashed across the barge. Loading was achieved by positioning and mooring the paddle steamer in such a way the steam winch coupled to blocks and tackle could haul the logs from their stockpile then lift them into position where the crew secured the logs with large chains. Because of the weight of the great logs the barges were turned several times so that the logs could be loaded evenly. After each barge was loaded they were shifted and moored, then the next barge was loaded, the loading operations took all day.

When the barges were ready to leave each vessel was positioned in the middle of the river, this manoeuvre was achieved by fixing a rope to the stern of the barge then rowing the rope to the opposite bank and anchoring it to a tree, the barge was then allowed to drift out from the bank, until the limit of the rope was reached, the barge moved by the river current and held by the rope would drift toward the opposite bank, when the barge was mid-stream the rope was cast off from the bank and a large chain dropped off the stern to drag along the river bottom behind the barge, this chain kept the barge from turning and in mid-stream as she drifted along with the current. The only way of manoeuvring the barges once adrift was by the use of the ropes and windlasses on-board, they had no rudder or tiller to control them and they were at the mercy of the river current. We drifted along with the current through the red gum forest, the river birds were amazing I have never seen such diversity of water birds; there were cranes, herons, egrets, ibis, spoonbills, water-hens, kingfishers, and a vast array of other forest birds.

After a few hours we entered the Barmah and Moira lakes, the river course ran through the middle of these lakes, the lakes formed one large body of water due to the high river level, the river course was defined by the rows of river red gums standing on what would have normally been the riverbanks. When we were passing through, the Moira Lake was wind blown and choppy, the Barmah Lake was glassy smooth like a millpond, it was quite a contrast, The Moira Lake being on the windward side of the Barmah forest probably caused this phenomenon. The Barmah Lake is a shallow lake and is a great breeding ground for native river fish; as a consequence it was well stocked with Murray cod and golden perch. The local aborigines had fish traps in the lake that dated back to ancient times and represented a long tradition of fishing in these waters. In those days the local aboriginal people lived at Cummerajunga mission station, the mission was situated on the banks of the river near Barmah.

Large ants known as bulldog ants were rife in the red gum forests and roamed freely around the logs on the barges the bites these ants inflicted were painful in the extreme and were avoided at all costs by the timber workers, I did not know of their fearsome reputation and would happily stand on them and kill them with my bare feet when the men found out about me doing this they were totally amazed, they had found them hard to kill with the back of an axe, or so they said. We had spent so much time running around barefoot our feet must have been as hard as iron.

|

|

|

| PS Adelaide with logging barge headed upstream. Museum of Victoria: Alban Pearce, 1987 |

Logging no longer takes place on the lower Goulburn, however it may take place once again in the future, with loggers proposing selective harvesting. Selective harvesting is used in the deciduous forests of Germany to maintain diversity. Conservation and commercial management of forests is possible, where there is cooperation and respect, when the goals are clear and conditions are right. Hopefully we can work towards this goal.

|

| Selective logging in redgum national parks up for debate again. ABC Rural. |

|

| My campsite on a high bank amongst an open woodland of grey box. |

|

| After the hot day I did not fancy cooking, so prepared and ate down at the boat. |

Watching sunset from my campsite.

All is peaceful.

Map showing the location of my campsite relative to McCoy Bridge.

Some thoughts on education and conservation by Will Trueman.

|

| Human actions driving change in the Goulburn River ecosystem. Source: Goulburn Broken Catchment Management Authority Biodiversity Strategy |