0 - 57 (57) km

Introduction

The Goulburn is not much of a river when it enters the Murray - most of the time. I live and grew up in Echuca, 18 kilometres downstream from the confluence of these two rivers. I have often visited the junction, as we call it, and rarely does the river push far into the Murray. Rather than speed up the river, paddlers know it as the place that the Murray slows down, as from this point on it comes under the influence of the Torrumbarry weir 80 kilometres further downstream. Occasionally however, it is a different story: when the Goulburn is in flood, it reaches the top of its 8 metre banks and, it's bed no longer able to contain it, it flows into the Murray through the forest in three different places. It has been known to cause the Murray to flow backwards as far upstream as the Barmah Lakes and even without a contribution from the Murray and the Campaspe, to cause widespread flooding in Echuca. When high volumes of water are moving down these rivers simultaneously, the effect can be catastrophic for the communities downstream.

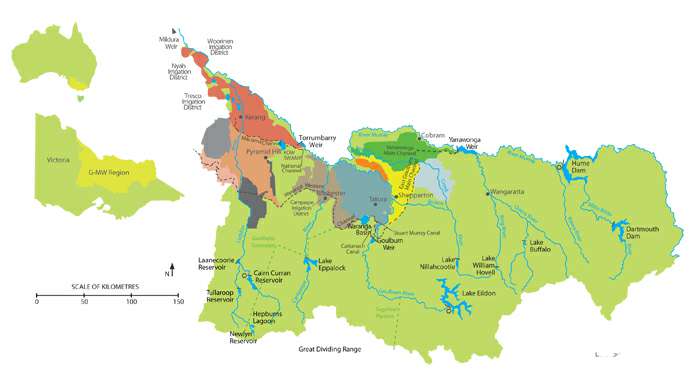

| Map of the Goulburn catchment Source |

|

| The Broken River, a tributary to the Goulburn. In the 460km from Eildon to Echuca the river changes from a fast flowing mountain stream to a meandering river, making it very interesting to canoe down. Picture Source |

In October 1824, Hume and Hovell left NSW to explore land between Cumberland and Westernport. Their party of eight included six convicts, two carts, horses and donkeys. On December 4th they crossed the Goulburn River at what is now Molesworth, seeking a passage from Sydney to Spencer

Gulf. Hovell recorded that there was “an abundance of fine grass and both hills and lowlands are thinly covered with timber. It is our opinion that we have not seen a more agreeable and interesting country since leaving home”. They camped on the banks of the Goulburn for two days at Christmas, s ‘in order that they might avail themselves of the fine fish which abound in its waters, as well as refresh the cattle.’ Hume and Hovell named the river after the then Colonial Secretary of NSW, Sir Frederick Goulburn. It paid to honour your sponsors even then. Of course it had many names before this. The Wurundjeri tribe and Taungurung language speakers are the traditional owners of the land, known as Murrindindi (ref 1, 2). Near Alexandra it was known as Koriella, lower down the valley, near Nagambie, it was known as Bayunga ref: http://home.vicnet.net.au/~goulburnriverclans/

|

Map showing the route Hume and Hovell took in their 1824 expedition, during which they were the first European settlers to record a crossing of the Goulburn River. Image source

|

|

| Map showing how water from the Goulburn is shared between valleys and cities in Victoria. Map Source; Goulburn Murray Water |

Given all these demands and the regulation that helps the river meet them, the river is surprisingly in good ecological condition. It is full of snags, which keeps larger boats and the problems caused by their wash away. Vegetation growth along the banks is strong minimising the effect of erosion by cattle and providing habitat for wildlife. After Shepparton, there is almost 200 kilometres of river redgum forest - now a national park. It was declared a heritage river in 1992. It is no wonder fishermen love it.

|

| Tahbilk Wetlands |

|

Our Toyota Echo packed and ready to go.

|

|

|

|

One of the first things Tim and I noticed was how clear the water was. We could easily see a metre through the water. It appeared crystal clear. We could see the full outline of our boats hulls as they glid through the water. Our paddles seemed shorter and leaves being tossed by the current deep in the river took on a life of their own as they reflected alternately, their own colour and then the colour of the sky.

I was struck how clear the water was and how healthy the water plants were. They swayed noiselessly back and forth in the current beneath our hulls as we passed over them.

It is 442 km from the base of Lake Eildon to the junction of the Goulburn with the Murray River. Goulburn-Murray Water estimate that it takes water in the river 10 days to travel that distance on average. We aimed to match that, although as we don't travel 24/7, it meant that we would have to do some paddling as well to achieve the same. That's the tiring bit. We had our first break just after Gilmore's Bridge, 18 km from where we had put in. It was a lovely flat area with a low bank which we could run the boats up onto and had plenty of shade to have a rest in as well. Officially there is no wild camping allowed between Eildon and Alexandra, but in an emergency, there are plenty of places to pull in.

Map source: Goulburn River Boating Guide GBCMA

| ||

Goulburn River profile, showing altitude, distance and time the river takes to reach its junction with the Murray River.

Source; Goulburn River Reach Report MDBA

Video grabs of what it is like to paddle on the river in this section.

The Upper Goulburn experienced a gold rush after the discovery at Jamison in 1854. In 1886, the 'Yea Chronicle' reported that the first crush of quartz and Prosser's Reef (just a few kilometres upstream from Thornton) had been most promising. Gold dust can still be found in streams by people panning for gold. More info: 1.

Thornton Bridge

|

| A flyfishing drift boat. We saw a guide in one of these expertly negotiating the eddies below the 'sump' rapids at Blue Gums. They call it streamcraft... and yes, they teach that too at the GVFFC (image source: visitmelbourne |

Thornton to the Alexandra (14 - 34 km from Eildon).

|

A great spot for a lunch break. We ran our kayaks up on the shore and were able to step onto dry land.

|

Goulburn Valley Highway (Gilmore's Bridge) 18 km from Eildon.

We were to pass under it twice today, once just after Thornton and then a second time just before Molesworth.

After 26 km, the Acheron a River enters from the South. Just before this, is one of the nicest situated caravan parks I have ever seen. It is called the 'Breakaway' and it was full of people who looked like they would prefer their patch of paradise remained a secret.

|

| Breakaway Caravan Park is set right on the river under shady, safe trees. Ideal for canoeists and fishermen. |

The breakaway gets its name because at this point, once the river reaches about 8,000 ML/d, flow starts going down the old course of the river, effectively turning the Goulburn into two rivers. There are remnants of levees in the mid-Goulburn. Indeed, levees on the riverbanks may have been the reason that the Goulburn has a breakaway near Alexandra. Two stories for the origin of the breakaway were heard — it was a neighbourly dispute with landholders on opposites sides of the riverbank building up the levees in competition until eventually one side blew and the breakaway formed with a new river course. Another version is that the breakaway started in 1912 following a big flood (the watercourse went through three properties, splitting them up). The breakaway was then further entrenched by feuding farmers raising levees on their own property to prevent flooding.

http://www.mdba.gov.au/sites/default/files/Reach-reports/GRR-Loch-Garry-to-River-Murray.pdf

Sudden changes, or flash floods happen following heavy rains in the area, because of the unregulated rivers which enter the Goulburn on this stretch. The Rubicon River, Acheron River, Spring Creek, Home Creek and Yea River are all known as 'flashy' because of how fast they respond to rainfall in their catchment. It pays to keep your eyes and ears open.

|

Just before Alexandra, the river disappears in a maze of willows. We took the left channel, which ended up only being a metre wide. Going off this 2012 aerial shot by Google Maps, it would have been better to try the right channel.

|

Maroondah Highway bridge near Alexandra. When preparing for your trip, or driving in, bridges give you an opportunity to check water level and flow. It is one thing to look up levels on a website, but nothing beats seeing them firsthand.

Alexandra to Molesworth (34 - 57 km from Eildon).

An afternoon break in the shade at Brooke's Reserve Canoe Camp, 2 km downstream from Alexandra.

At times the river runs dramatically right into the hills that define its valley, bouncing off them as if they were a mirror, or running alongside in a silent challenge.

In many places willows cover the banks. Sometimes these grow so thickly that there is only 5 metres of river left to paddle on. If they manage to take a toe hold on a gravel race in the middle of the river as well as on the sides, then watch out. This happened at around 34 km into the trip. Rounding the bend it was not at all clear where the river went to. In truth, most just went straight through the willows which acted as strainers all the way across the river. Slowly edging our way along the bank, (because it is easier to pull out there if you are in trouble than in the middle), we noticed a metre wide gap. Once through, the river opened up again. When stones or trees channel the current into a narrow shoot, its speed increases dramatically. On one occasion, we were able to push our speed up to 18 km/hr, however or average was 9.8.

Sky and riverbanks reflected in the still water.

|

An old and collapsing private bridge, with grass growing on it, about 5 km before Molesworth. |

Map source: Goulburn River Boating Guide GBCMA

|

| Passing under the Goulburn Valley Highway bridge at Molesworth. There are actually two bridges; the first is an old rail bridge which is now used for the Goulburn River High Country Rail Trail (walk / cycle / ride) which follows the river off and on, from Mansfield, through to Tallarook. |

Our camping spot at Molesworth, about 150m from their boat ramp. Having a kayak trolley meant that we didn't have to unpack to move the boats, which saved time and energy, both of which we were short of at the end of the day.

In camp, Tim and I enjoyed a good hot shower and a well flavoured trangia meal - the secret ingredient being a curry sauce. I was glad we had that, as I had also experimented with tinned ham - which unfortunately looked and had the consistency of dog food.